World’s First Circumnavigation Aerial Flight (revised 15APR24)

From The First World Flight by Lowell Thomas

A Cross Between The Right Stuff, the First Man on the Moon and the Beatles Coming to America. It was the first aerial circumnavigation of the earth, the first crossing of the Pacific and the North Atlantic Oceans.

Interactive Google Map with Photos and Videos

After heading west for 175 days, 26,300 miles around the world, in open cockpit biplanes, The Chicago and New Orleans set back down in Seattle, 28 September 1924. They had no navigational aids other than rudimentary maps and their eyeballs. The Seattle crashed into an Alaskan Mountain near Dutch Harbor and The Boston went down in the North Atlantic. All crews survived.

Other competing countries, that had either tried it, or were planning to included Argentina, Britain, France, Italy and Portugal. The Army Air Service, as it was known then, enlisted the help of the Army, Navy, Diplomatic Corps, Bureau of Fisheries, and Coast Guard as well as 22 countries to pull this colossal achievement off. It was the 1920’s equivalent of sending a man to the moon.

The following copy in italics are text directly from the 1925 book: The First World Flight

The behind-the-scenes Architect of The First World Flight:

Brigadier General Billy Mitchell

Recommended on Audible

Introduction by General Patrick

On September 28, 1924, two airplanes landed at Seattle, Washington, thus completing the first flight around the world. These planes and the men they carried had flown 26,345 miles, their actual flying time being about 363 hours. They had experienced all varieties of climate from the cold, to the snow and ice of Arctic regions, to the tropical heat of India.

These World Fliers have frequently been called the Magellans of the Air. They have now completed a modest record of their achievement. In this, they contrast with the great mariner who first sailed around the world, for we are told that no record of his exploits was left by Magellan himself.

The story of this, the first flight around the world, is evidence of the skill and courage of those who were sent forth upon this mission. It also evidences the fact that the airplanes in which they flew were worthy products of the designers and of the manufacturers who were responsible for their building. They were the best planes of their type which could have been produced anywhere at the time when they were constructed. But when, in future years these planes are viewed in the National Museum, people will no doubt wonder, contrasting them with the airliners then in use, that men could be found who were bold enough to undertake so hazardous an air voyage in such small and fragile craft, just as today, when viewing the Leviathans which ply the ocean, we contrast them with the cockleshells in which Columbus ventured forth on the unknown and uncharted seas.

Of what these World Fliers did, we may well be proud, and I commend their story to our people who have always admired those who are willing to venture into new fields, to show themselves to be men, undaunted by dangers, resourceful and unafraid.

Mason M. Patrick

Major-General, AS

Chief of Air Service

FOREWORD BY THE FLIERS

Our flight is over and our story told. We are now bidding au revoir to each other, so this may be our last opportunity of speaking collectively as the so-called ‘six world fliers.’ But we like to think that this United States Army Air Service flight, in which it was our privilege to play a part, is just one more step in advancing the history of civilization. And we hope that it will contribute thereto by impressing you with the boundless possibilities of aerial transport. Someday – soon perhaps – we shall look back and smile at the difficulties we encountered, for we are now entering upon a new era, in which travel by air will he as commonplace as travel by covered wagon for our forefathers. – from The First World Flight by Lowell Smith

World flyers (left to right) Lieutenant Jack Harding (28), Lieutenant Eric Nelson (35), Lieutenant Leigh Wade (28), Major Frederick Martin (42), Lieutenant Leslie Arnold (29), Lieutenant Lowell Smith (32). They are wearing black armbands in honor of former U.S. president, Woodrow Wilson, who had recently passed away.

Keys to Success:

As conceived by Brigadier General Billy Mitchell

- Four planes instead of one

- Flying west vs east to time the seasonal weather

- Logistical supply chain

- Diplomatic cooperation

- Pilots with exceptional navigational skills (Lowell Smith)

- Pilots with exceptional mechanical skills (Erik Nelson & Jack Harding)

- The Donald Douglas aircraft

- Interchangeable pontoons and wheels

- Luck and divine providence

Four of these Douglas World Cruisers, with eight men, set off on an international race 6 April, 1924 from Sand Point Field in Seattle Washington: The Boston, The Chicago, The New Orleans and The Seattle.

The route had pre-positioned logistical bases, divided into 7 divisions around the world, including ground support and spare parts that included 50 extra Liberty engines, 14 extra sets of pontoons, and enough replacement airframe parts for two more aircraft. Maintenance was the key to success, and the reason an onboard co-pilot/mechanic was so vital to the mission.

The Douglas World Cruiser (DWC)

Planning & Support Team

The Douglas World Cruiser

The Douglas World Cruiser aircraft was modified from the Douglas DT-2 U.S. Navy torpedo plane design. This flying machine would ensure the success of the Douglas Aircraft Company and later, the McDonnell Douglas Corporation.

M.I.T. educated Donald Douglas, the engineer who built the planes in which man first circumnavigated the world by air. (a/i enhanced)

Each plane measured fifty feet from wing tip to wing tip and thirty-eight feet from propeller to rudder. Each could carry four hundred and sixty-five gallons of gasoline, thirty gallons of oil, and five gallons of reserve water. Empty, it weighed nearly three tons, and loaded, with crew of pilot and mechanic, over four tons.

The chief instruments on the dashboard are the tachometer, recording the revolutions per minute at which the engine crank-shaft turns the propeller, the air-speed indicator, engine ignition switches, ampere-meter, volt-meter, oil-pressure gauge, gasoline-pressure gauge, altimeter, an ordinary airplane compass, a new earth-inductor compass (which rarely worked)1, a bank-and-tum indicator comprising two small gyroscopes for flying in fog, an automatic ignition cut-out switch, six gasoline control valves; also altitude controls to change the proportions of gasoline and air fed to the engine at varying heights, and an engine primer for starting in cold weather.

The pilot sits in a roomy cockpit directly behind a 420-horsepower, twelve-cylinder Liberty engine, on an aluminum bucket seat. He has a wheel in his hand like an automobile’s, but set at a steeper slant to his body; the rotary motions of the wheel operate the ailerons (the hinged horizontal sections of the wings) and are used to keep the plane balanced. At his feet is a bar which operates the rudder in the tail assembly and steers the ship to right or left, while the driving post on which the wheel is mounted (known to aviators as the ‘stick’) can be moved to or from the body, thereby operating the elevators (the

winged section of the tail assembly) and controlling the upward and downward movements of the plane.

The Liberty engine was used on the first transatlantic flight by the NC-4. It powered most of the JN-4 Jenny’s, were used in rum-running boats during Prohibition, and were found decades later in some WWII tanks.

The Liberty Engine was also used on the GMB Bomber which flew the first Round-the-Rim flight in 1919. The first flight around the perimeter of the continental United States. The 10,000 mile flight was crewed by Sgt. John Harding, Jr. as a aircraft mechanic. This was the set-up for selection of the World Flyer team.

The assistant pilot, or mechanic, sits in the rear cockpit. Behind and beneath him in the tapering fuselage is a roomy baggage and tool compartment. Both cockpits are of identical size and contain the same controls so that the plane may be navigated by either occupant. Small transparent shields·; protect the pilot and mechanic from the powerful air stream of the ship in motion.

“With preliminaries completed, all crew members (including the two alternates) were assigned late in 1923 to Langley Air Base, Virginia, for several weeks of intensive study in global navigation, survival, engineering maintenance, and for checking and double-checking the overall flight plan, and making necessary modifications. In December of 1923, the prototype world cruiser arrived at Langley and flight training began. As a land-based plane, the world cruiser posed no training problems, but the float-plane configuration would be a new experience to some. To solve that part of the training, the Navy assigned

Commander Ramsey to instruct in float-plane technique.”2

There were four planes to fly with two airmen each totally 8 men, and two alternates. A fifth plane was held in reserve.

| No. 1 | Seattle | Fredrick Martin |

| Alva Harvey | ||

| No. 2 | Chicago | Lowell Smith |

| Leslie Arnold | ||

| No. 3 | Boston | Leigh Wade |

| Henry Ogden | ||

| No. 4 | New Orleans | Eric Nelson |

| John Harding |

By mid-March 1924, the news of other nations beginning the race, keyed up the Americans to get going. On March 17th, the four World Cruisers left Clover Field in Santa Monica, for the “dry run” up to Seattle Washington, the official starting point.

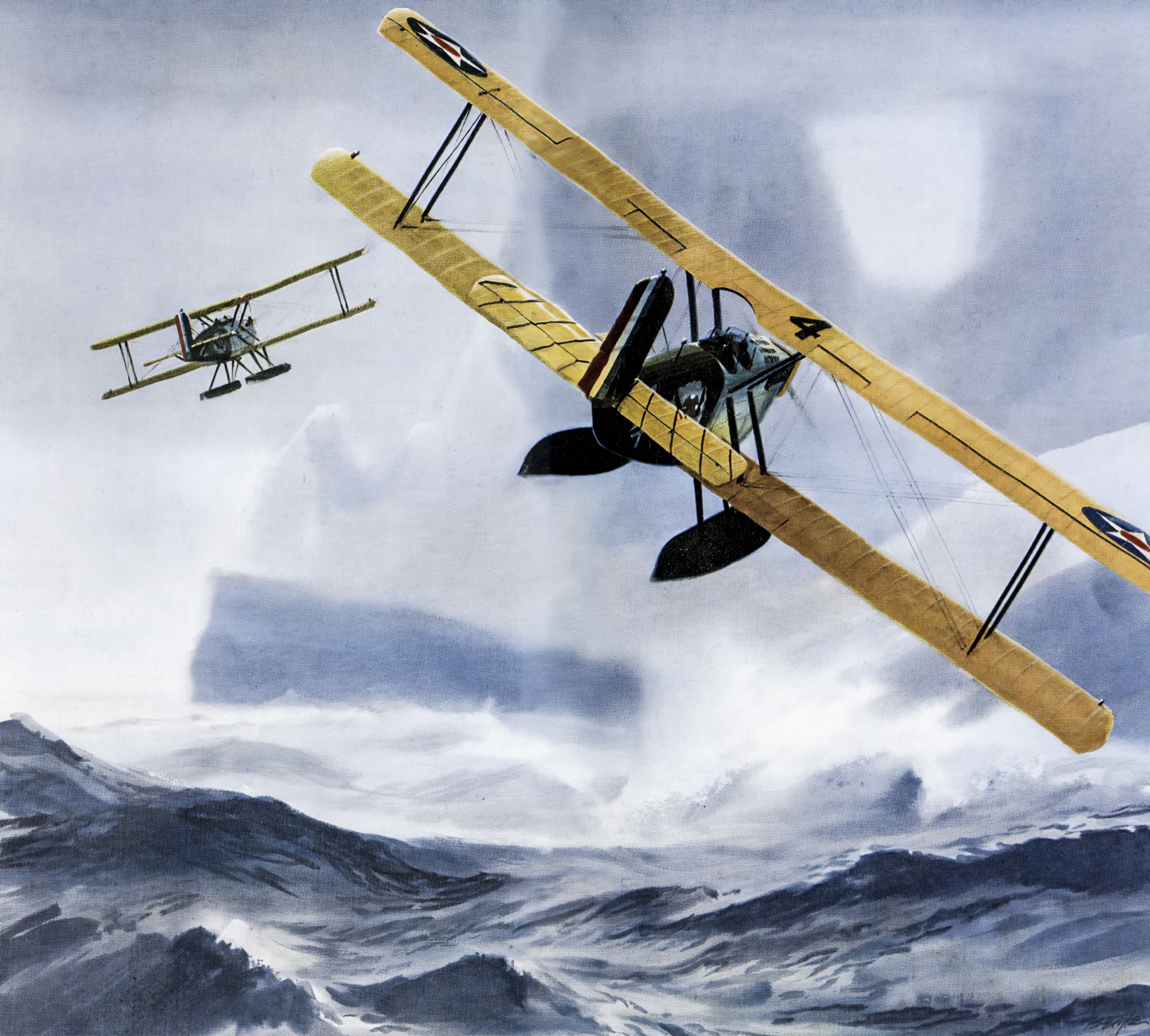

THE FLAG-PLANE SEATTLE GETTING READY TO TAKE OFF FOR ALASKA

Major Martin kneeling and Sergeant Harvey standing on the fuselage

From Seattle to Prince Rupert

Plunging on through drenching rain, and rounding Cape Caution, we saw the great swells rolling in from thousands of miles across the Pacific. Fully forty or fifty feet high those cold gray waves looked to me as I leaned over the edge of the cockpit. Hurling themselves against the rocky cliffs of Cape Caution, the great rollers burst into a shower of spume and spindrift that shot hundreds of feet into the air.

It would have been fun to watch the old waves pounding against Cape Caution, but I wondered what would happen if we had to flop down in the middle of those angry seas. You can land in fairly rough water, but never in such wild, angry seas as these were. This was about the most vicious stretch of water that any of us, excepting Erik, had ever seen, and even our Viking got a thrill out of it.

Sometimes we were flying through driving rain, sometimes through fleecy snow, again through sheets of sleet, and twice through squalls of hail that pelted the fuselage and wings like a flock of machine-gun bullets all striking at once.

Alaskan Blizzards

The beach was covered with snow, and the air around us was filled with it. Everything was one color and we might almost have been flying in total darkness. The only help was a strip along the beach where the waves kept washing and melting the snow, and this in contrast to the gray-white color of everything else appeared as a narrow black ribbon. We would drop down and cling to this line until we came to a bay, then we would shoot straight across until we picked up the beach again on the other side. Twice, when the density of the storm lessened for a few moments, we passed over villages blanketed with snow, but with many of the roofs all caved in: they were abandoned mining towns, ghost cities of the gold-crazed adventurers of the past.

WE ANCHORED lN FRONT OF AN ALASKAN SALMON CANNERY AT THE HEAD OF RESURRECTION BAY – today this is called Lowell Point (a/i enhanced)

Had there been a cliff or promontory jutting out, the chances are that all four planes would have crashed headlong into it. We couldn’t see far enough ahead to have avoided it, and we were flying too low to have gone over it. But luckily the coast was straight and the beach clear.

Sometimes we flew so low that our pontoons almost dragged on the water.

Forced Landing of the Seattle

Terrific blasts sweep off the mountains and are known as “Willie-wa.” Although only of short duration, they often reach a velocity of from fifty to a hundred miles an hour.

Martin & Harvey Lost in Alaska

From Chignik to Dutch Harbor

Our ceiling now was about two hundred feet. But somehow that body of water never got any nearer. Instead we were approaching fog. I was now strongly inclined to turn back to Chignik and start all over again by way of the original course. But, as we had come this far and the water seemed near, we kept on. The fog grew so dense that it drove us down within a few feet of the ground. Still we found no water. But feeling certain that we had left the mountains behind us, I thought it would be safest to climb over the fog, which I felt sure would only extend for a short distance.

In order to make sure of getting all the way to Dutch Harbor, we had taken on board two hundred gallons of gasoline and oil. With this heavy load she climbed slowly. We had been gaining altitude for several minutes when, suddenly, another mountain loomed up ahead. I caught a glimpse of several dark patches, bare spots where the snow had blown away. A moment later we crashed.

The right pontoon hit first and struck an incline right on the top ledge of a thousand-foot precipice where the mountain tapered upward in a gentle slope. The plane came to a final stop about two hundred feet up this grade. The fuselage keeled over on a forty-five-degree angle. The force of the impact drove the right pontoon under the fuselage and jammed it up against the left pontoon. The pontoon struts were, of course, splintered and tom loose. The bottom right wing was demolished, and the one above it driven halfway back to the tail.

For eleven long days they made their way over rough terrain, blinding blizzard’s and living off the land. They followed a creek to Moller Bay and then to Port Moller on the Bering Sea. Thus ended the adventures for Major Martin, Sarget Harvey and The Seattle of the Around The World Flight.

At two o’clock that afternoon, we came to a desirable spot to camp, which we decided to do because I was snow blind and helpless. Here we found plenty of deadwood for fuel, and with dry grass from a marsh we made a bed and managed to get about four hours’ sleep, our first real rest since the crash. It never took us long to prepare a meal, for we usually had nothing but our emergency liquid ration. According to the instructions we had been given, two teaspoonfuls per person were supposed to constitute a meal, but we increased this ration to three.

On the morning of May 6th, we continued our march through the swamp, and finally reached a valley where this stream passed through the mountain range. The snow was deep and the crust was not strong enough to hold us, so struggling through it was tedious work. As we were both very weak, we halted at 3 P.M., and Sergeant Harvey, after investigating, reported that he had seen a body of water about three miles to the south. But we were too exhausted to go on that night, and again camped in an alder thicket.

By seven-thirty the next morning, we arrived at the shore of the water, which Sergeant Harvey had seen on the previous afternoon, and there we saw a cabin only half a mile away. Here we found a small cache of food, including flour, salted salmon, bacon fat, baking powder, dried peaches, condensed milk, sirup, and coffee. There was also a quantity of wood cut for a small heating stove, and it looked as though the cabin might have been occupied the previous day, although the bedding had been removed.

They were spotted and picked up the next day by a fisherman, after 12 days in the wilderness.

Willie-Wa

Not only were the angry winds referred to as Willie-Wa, a problem in the air, it was quite a nuisance on the surface too. Even anchored, the planes were continually blown away from their moorings, so that a 24 hour watch was required in order not to lose them. There were numerous occasions were they had to be rescued throughout the Alaskan leg of the voyage. These mountain-wave angry winds would reach up to 75 miles per hour.

Aleutian Islands to Soviet Territory

Attu Island was the last U.S. island in the Aleutian chain. From here, they planned on flying to Japanese Territory in the northern Kuril Islands. But due to bad weather they were forced to head north east into Soviet territory, which they had no permission to do. They landed in the Bering Sea just off the shore of the Soviet Komandorski island group. This attracted the attention of the Russians:

At 3:05 AM we arrived over Copper laland, the most easterly of the Komandorski group: says Smith. ‘That bleak bit of land out there in Bering Sea sure looked good to us. From a promontory, marked Polatka Point on my map, I headed northwest toward Bering laland, the largest of the group, and at five o’clock saw a dent in the coast and the wireless towers of the Soviet looming above the village of Nikolski. About the same moment I spotted the Eider five miles offshore. But it was too rough for us to come down away out there, and her officers, realizing this, steamed to three miles from Nikolski and dropped buoys while we circled above the island.

Afterwards we were told that newspapers back home described how these Komandorski Bolsheviki of Nikolski had told us to “get outski.” But that was all bunk. They were exceedingly courteous, although they naturally did want to know who we were, where we had come from, why we were there, and whether we had permission to land. We explained that we had been forced to put in at their islands because of storms to the south. When we assured them that we were birds of passage winging our way round the world, and that we merely desired to remain overnight, they asked us to stay on board the Eider and not go ashore. That was exactly what we wanted to do, anyhow, and they knew it. In the meantime, they said they would send a wireless message to Moscow to see what Comrade Trotsky had to say.

We heard nothing more that day officially. They sat around smoking cigarettes and chatting for a while. Upon returning to the village, they showed their good-will by sending out a flagon of vodka – which, however, we did not drink.

Just as we were getting ready to take off, out came the bearded committee in their little boat with word from Moscow that we could not be allowed to stop there. We thanked them for their courtesy, and chuckled to ourselves a bit because we had already remained as long as we wanted. So I asked them if they would mind pulling their boats off to one side a little. Then signaling to Erik and Leigh we all “gave her the gun” together, and I suppose the Russians are still stroking their beards and wondering what it was all about.

Advance Man for Japan

The man in the black stocking cap is Linton Wells. Associated Press representative, who followed the flight all the way from Bering Sea to Baluchistan. (a/i enhanced)

At first Nutt encountered obstacles with the Japanese authorities, who feared the flight might be an excuse for obtaining airplane views of their fortifications. But once Lieutenant Nutt and Major Faymonville had succeeded in convincing them that America contemplated nothing of the sort, the Japanese joined heart and soul in making the Flight a success and gave the boys a splendid reception when they arrived in their territory. They laid out a special course for the Fliers to take, however, and instructed them to follow this route in order not to fly over points of strategical importance. It was also requested that the boys should deposit their cameras with the commanding officer of the U.S.S. Ford until after the departure from Japan.

Reaching the Kuril Islands

Past the Soviet Union, flying south across the western rim of the Pacific coast, the flight of three finally landed off the shore of Paramushiru, which at the time was Japanese territory in 1924. It was the northern most tip of the Kuril Islands at the time [today Russian territory].

The navigation for this 585 mile stretch of the mission was quite accurate. They only missed the island off Paramushiru by about a mile. Using Dead Reckoning navigation, one of the most import computations is for wind drift. This was accomplished by dropping a smoke bomb from the plane and comparing it with the directional peg lines drawn along the rear of the fuselage in 5º increments.

They were taken aboard the U.S.S. Ford for the night. From Lowell Thomas:

A gale blew that first night at Paramushiru, and it was a stem-winder. The officers insisted on giving us their bunks, and the one I occupied must have been a little wider than usual. At any rate, there was nothing I could brace myself against, and when the ship rolled, I rolled, and my recollection is that the ship never stopped rolling. The cabin was full of trunks, shoes, and all sorts of things that kept slamming back and forth. On one side was a bookcase, and once when the destroyer gave a lurch the books all tumbled out on top of me. I got up and put them back carefully. But a moment later she gave another lurch with the result that Webster’s Abridged Dictionary hit me on the jaw and nearly broke it; Mark Twain’s “Innocents Abroad” plumped on my stomach; while a little volume of “Much Ado About Nothing” nearly put out one eye. Just as I reached up to switch on the light, Irwin Cobb’s “Roughing It De Luxe” caught me in the ear. Never had I been so intimately in touch with literature!

In Tokyo (Tokio)

No event during our hurried visit to the capital of Japan impressed us so deeply as the luncheon given in our honor by the Faculty of the University of Tokio, at which the President, Dr. Yoshinao Kozai, addressed us in English as follows:

“Officers of the Army Air Service of the United States, It is an honor and great delight to us to welcome you to our University – you, who have come to our shores over the seas, through the air. All here assembled, both the Faculty and the members of the Aeronautical Research Institute of Japan, cannot but admire your dauntless spirit and congratulate you on the success you have achieved.

At the same time we envy you, for your daring is backed by science. Indeed it is the happy union of courage and knowledge that has gained you your success and this honor of being the first of men to connect the two shores of the Pacific Ocean through the sky. This same spirit and skill, I am sure, will soon make you the pioneers of aerial flight around the globe.

Looking a little into the past, it is to your nation that the honor is due for having produced the pioneers of aviation, Langley and the Wright brothers, and during the two decades that have followed their first successes in the air, the progress of aviation accelerated by your fellow citizens has been simply marvelous. Your pioneership is a manifestation of your valor which implies daring and indefatigable spirit in conjunction with deliberation and endurance. Your success is not merely a result of adventure, but it is the fruit of study and research in the wide and complicated domains of physics, chemistry, mechanics, and meteorology.

Gentlemen! Your honor is, of course, the pride of your nation; but the honor and pride are to be shared by all mankind, because they are a manifest expression of moral and intellectual powers in the human race – the will, ability, research, means and methods, all illustrate through your success man’s control over nature.

More than four hundred years ago slow sailing vessels carried Christopher Columbus across the Atlantic. Two centuries later, your pioneers crossed the Rockies with weary horses and carts.

Nearly a half-century elapsed before the two oceans, the Pacific and Atlantic, were connected by rail. And now you are encircling the earth by machines flying through the sky.

Again I say, we admire and envy you. Again I say that your honor is to be shared by all mankind.

Wing west ward, farther and farther to your home! Then start anew toward the west and come again to our shores, then on to our neighbors and to yours, and through all the continents of the world! Thus through your efforts and successes will the nations of the earth be made closer friends and neighbors.

To the west, east, north, and south, we shall everywhere follow your journeys with admiration and congratulation! We bid you God-speed!

Their Finest Hour

The British were on their second World Flight attempt. What is so astonishing by today’s standards, is The U.S. helped the British flyers along the way, and they helped us too. So did the Italian’s and the French.

…when there came a knock at the door, and the Japanese “boy” handed me a telegram: MacLaren (British pilot) crashed at Akyab [Myanmar aka Burma]. ‘Plane completely wrecked. Continuants of flight doubtful.’

Without a word, I handed it to Lieutenant Smith, and he read it and passed it on to the others, and I think I then remarked: “Two years’ work gone west!, I thought of Major MacLaren and his companions at Akyab, their beautiful machine a wreck, and that he must be thinking of how he could get the spare one that I was that very day loading on the trawler’s deck in Hakodate Harbor, five hundred miles to the north of Tokio, as a spare machine for our Pacific flight. A thousand thoughts were tumbling over each other in my mind, when Lieutenant Smith said, We’ll get the machine to MacLaren somehow. Let’s come upstairs to Commander Abbot’s bedroom and have a talk with him. ‘Within five minutes, these great-hearted sportsmen had roughed-out practical plans – how Captain Abbot, on his own responsibility, would rush a destroyer to Hakodate and then load and carry the huge cases to Nagasaki, where his beat, so to speak, ended, meanwhile cabling Admiral Washington, commanding the American Asiatic Fleet, for permission to take them farther – all the way to Akyab if necessary.

The First Lord of the Admiralty told Lowell Smith that he would gladly place the British Navy at the disposal of the World Flight for patrolling the North Atlantic, if Smith wished. However, it was not necessary for him to avail himself of this sweeping offer because the American Navy was already detailed for the task.

” Life is mostly froth and bubble, Two things stand like stone: Kindness in another’s trouble, Courage in one’s own.” (Adam Lindsay Gordon)

Saturday night, May 31st, we finished overhauling the planes, and at 8 A.M. next day were on the lake ready to start for China. The Chief of the Japanese Air Service and a special train packed with officials arrived from Tokio at dawn to see us off. We were much surprised to see them, but they replied that they looked upon the circumnavigation of the world by air as an event sure to usher in a new age, and an age in which they intended Japan to play a leading part.

Seeds of War

Although our visit to Japan followed right on the heels of the passing of the Japanese Exclusion Bill by Congress, at a time when feeling was running high against Americans, we saw not the slightest evidence of it. In fact, we were amazed at the genuine enthusiasm shown by the Japanese educational authorities over our American attempt to fly around the globe. Throngs of children met us everywhere, and the day we went by train from the naval air base to Tokio, school children were drawn up in military formation to see us and give us their Japanese yell at every station where the train slowed down even for a moment. Although we hadn’t yet flown a fifth the way round the world, they seemed to feel that ours was the type of undertaking that might inspire the younger generation.

Passage of the Immigration Act has been credited with ending a growing democratic movement in Japan during this time period, and opening the door to Japanese militarist government control.3 It was signed into law by President Coolidge the day the fliers were being entertained in Tokyo.

China

When the Boston and New Orleans reached Shanghai, the Yangtzb-Kiang was swarming with Junks and Sampans (a/i enhanced)

They left Kagoshima Bay, Japan at 8:25 on the morning of June 4th. It would be the first clear day of flying since leaving Seattle.

We flew across the junction of the Yellow and China Seas. An hour off the coast we had passed the U.S.S. Ford, the first of the destroyers detailed to keep an eye on us. Forty miles off the China coast we could tell we were approaching the mouth of a great river because the sea changed color from deep blue to green, and then, as we drew nearer the mainland, it turned to liquid gold in the sunlight.

We knew we were approaching the delta of one of the largest rivers of the world, the Yangtze-Kiang, which traverses a stretch of country from source to sea greater than the distance between New York and San Francisco.

As we flew across the mouth of the river and drew near Shanghai, we were amazed at the number of craft below us. The river teemed with tens of thousands of junks, sampans, and steamers. But we found when we came down that the harbor-master had held up all traffic in the river for hours. Just in one bunch there were over two hundred and fifty boats loaded with fish, and these hardly represented a hundredth part of all that Bedlam of boats. Not knowing just how much space we should require, the harbor-master had cleared several miles of water-front in order to save us from the fate of D’Oisy, the French world flier, who had crashed on the outskirts of Shanghai a few days before.

The French crash was probably caused by the congested river traffic, so the Douglas World Cruisers were given a safe landing zone because of that tragic ending of the French voyage.

About this time came word that the Italians, Portuguese and Argentinian’s were also well underway.

After the reception on the excursion steamer, we rowed back to our planes and went to work. But in so doing we disappointed people ashore who had drawn up the reserve militia, mounted and in full regalia, to receive us. We were sorry to miss meeting these folk, but I am afraid we were the cause of similar disappointments all along the line. Our work was first, for we were not on a joy ride. Often we finished our work by lantern light and then were up again before dawn.

The take-off from the bay was difficult, as were most water departures wherever they went. Leaving from the Amoy Bay on the China coast:

Something had to be done to prevent the planes from being crushed by those thousands of boats. So we backed off a few feet, and then shot the boat full speed ahead. Some of the sampans capsized, throwing the occupants over into other craft or into the water. It wasn’t long until we had cleared a space. From then on the boatmen kept at a respectful distance.

Flying down the coast of southern China, they startled a village, like they often did, of people that had never known of an airplane:

Evidently the natives of Luichow Peninsula had never seen airplanes before. We flew only about five hundred feet off the ground, and as we came roaring into view we could see Chinese running in every direction. When we caught up with them, they would swing off either to the left or to the right to avoid the dragons that seemed about to gobble them up.

Indo-China (Vietnam)

The flyers had to repeatedly snub receptions that were held all along their route, due to the urgency of the mission. The first priority was working on the planes after each flight. Only then, would they entertain dignitaries:

We had lightened our loads by throwing overboard every unnecessary thing, including all our clothes excepting those in which we flew. This meant that we couldn’t attend functions unless we could borrow suitable apparel. But by now we had reduced the borrowing business down to a fine art. As soon as we boarded a destroyer at the end of a day’s flight, we would size up the officers. Then, without their being aware of our evil designs, each of us would pick out an officer about our own size whom we would later relieve of a pair of white trousers, socks, shoes, white shirt, tie, and sun-helmet. This would enable us to board the waiting rickshaws and sally forth to the evening’s festivities as snappily groomed as any cake-eater of the China coast.

By now the motor was red-hot again and pounding badly, so we were obliged to turn out to sea, all the while scanning the country for some sheltered lagoon where we might come down. I spotted one at last, some three miles inland, so we hopped across the jungle and dived toward it. Nor were we a minute too soon. As we started to glide toward the lagoon, everything in the motor seemed to be going to pieces, for a connecting rod had broken and poked a hole through the crank-case. I couldn’t tell at what moment the ship might catch fire. Immediately they landed, Arnold jerked loose his safety belt, grabbed the fire-extinguisher, and bounded over the side.

Fortunately they were not on fire. But they were stranded on a lagoon in a remote comer of lndo-China, with a wrecked motor and without food or drinking-water – none too pleasant a situation.

French Fopaux

At a sidewalk cafe in French controlled Saigon, Indo-China:

Calling the head waiter, we started to give him our orders, when he interrupted and said that he could not serve us and that we would have to leave. When we asked the reason, he said that no one without a coat could be served at that cafe! We fully appreciated that it was somewhat uncommon for Europeans to be without coats, and we tried to explain who we were and how, as Air Service officers, we could put on our naval friends’ trousers and shirts in order to come ashore, but that it was impossible for us to wear their tunics and masquerade as members of another branch of the United States Government service. All he said to this was that he knew who we were, but that it made no difference, and we would have to go away at once.

This frosty reception didn’t increase our enthusiasm for Saigon and we voted the city a “washout.” To make the affair all the more unpleasant, the Frenchmen sitting at adjoining tables apparently relished our embarrassment and sided with the café management.

Bangkok

We were delighted with the Siamese, and particularly impressed by the intelligence, courtesy, and charm of the upper classes. We liked them the instant we met them. In fact the welcome of Bangkok was so warm that once again our planes were in danger of being crushed by hundreds of sampans. But the Siamese officers strung circles of police boats around each Cruiser for protection. Just before we started ashore with Mr. Dickinson, the American Chargé d’Affaires, a squadron of planes appeared over the cocoanut palms and banyans. Right down the Menam River they flew in formation. When directly above us, they dipped and gave us the salute of the Siamese Royal Air Force. Siam is indeed a land of contrasts. Around us were sampans filled with naked people, while overhead flew the airplanes introduced by King Rama VI, an Oxford man.

From Siam to Burma

To fly from Siam to Burma, Commander Smith had to decide whether to go around the Malay Peninsula, or fly over it. If the former, they were faced with a flight of nearly a thousand miles across the Gulf of Siam and the South China Sea, to Singapore near the Equator and thence up to Rangoon. Their planes were still equipped with pontoons, so it was advisable to keep over water as far as possible until the arrival in Calcutta, where they were scheduled to change to wheels for the flight across India. If, on the other hand, they flew over the northern end of the Malay Peninsula, and ran the risk of engine failure over a jungle where a forced landing meant disaster, then a flight of only one hundred and thirty miles would take them overland from one sea to another and shorten their journey to Rangoon, by over eight hundred miles. Smith decided on the short cut.

On nearly every leg of their journey round the world, the Fliers encountered some new phenomenon. This ‘jump’ across Malaya was no exception. Just as the giant jungle creepers twine themselves around trees and strangle them, so the strange air-currents from the forest reached up and gripped them with unseen but ferocious power.

Rangon

That first night in Rangoon, another ill-wind blew our way. We were sleeping off the effects of our nerve-racking flight across the Malay jungle, when a Burmese river-boat came drifting down the Irrawaddy on our planes. We had moored them well out of the main waterway. But the Burman at the rudder of this particular boat must have been asleep, or secure in the knowledge that his boat was heavier than anything on the river with which he was likely to collide.

When the sailors from our destroyers guarding the planes saw this huge hulk, with its sail silhouetted above them, it was almost too late for them to prevent her from riding down all three Cruisers. The New Orleans happened to be the nearest plane in line. Realizing they had only a few instants in which to save her, one of the sailors clambered up the stem of the Burmese boat, clipped the helmsman in the jaw and took charge. The others in the guard launch threw their frail cockleshell between the plane and the oncoming Burman. A collision there was, but thanks to the sailors it was only a glancing blow. However, it smashed half the bottom left wing of the New Orleans and made it certain that we should now be delayed for a number of days, no matter how Smith’s attack of dysentery progressed.

Calcutta, India

IN ORDER TO CHANGE FROM PONTOONS TO WHEELS (a/i enhanced)

Benares, India

Allahabad, India

SHIPS OF THE AIR AND OF THE DESERT MEET AT ALLAHABAD

IN THE HEART OF ROMANTIC INDIA (a/i enhanced)

Ambala, India

Meanwhile, the Royal Air Force pilots in Ambala entertained us at their mess, and we had a particularly enjoyable evening, partly because it was not marred by a lot of unnecessary speeches.

These lads were horror-struck when they saw us climb from our planes wearing the regulation leather helmets used in temperate climates, and they told us harrowing tales of how men went mad in the air as a result of the tropical Indian sun penetrating their skulls. While flying along the Afghan frontier, where the Royal Air Force has a patrol, they told us that pilots sometimes did insane stunts that could only be accounted for by the sun. So not wanting to arrive in Baghdad crazy as loons, we were very glad to accept their kind offer of specially constructed aviation sun helmets made for India.

Karachi, India (now Pakistan)

Everything went along well until we were about an hour out of Karachi, when the motor in the New Orleans decided to have a Fourth of July celebration on its own account and started to fly to pieces in mid-air. Looking back, we saw spurts of white smoke pouring from Erik and Jack’s ship. Throttling down, we dropped back and flew around the New Orleans. We could see oil all over the side of the ship and had a fair idea of what had occurred. The country over which we were then flying was open desert. But instead of sand, the ground was baked mud, which had cracked into gaping seams, so that if they had been forced to land the plane would have been wrecked.

Thirty-five miles or so to the east of us we knew there was a railway line called “The Northwestern” which runs from Lahore to Karachi. Erik signalled that he intended to fly across and follow the railway in to Karachi, so that in case of a forced landing they would at least be near to a line of communication.

The cause of the engine failure was never ascertained, but what had actually happened was that one piston had disintegrated and both exhaust springs flew out through the exhaust stacks. Then two other cylinders went to pieces. The exhaust valve broke the connecting-rod and all the big pieces of the rod and wrist pin were thrown through the bottom of the crank case into the cowling. One of the flying chunks of metal tore a hole in the wing. Another hit a strut. A third nearly hit Jack. By now the motor was jumping up and down in alarming manner, and the oil mist was pouring out through the open cylinder in

great clouds.

Erik first knew he was in for trouble when his motor started slowing down. Both men were standing up in their cockpits watching for fire. Throttling back, they descended in order to look for some possible place to land. There was none. So Erik headed east, as has been explained, toward the railroad. When he increased the revolutions of his engine, pieces of metal again started shooting out of the exhaust pipes, one of which grazed Jack’s temple when he put his head out over the fuselage looking for a landing ground.

It was all Erik could do, from then on, to keep the engine turning at 1100 revolutions a minute, which is just enough to stay in the air without ‘stalling,’ for the normal rate is 1640 revolutions. All the rest of the way to Karachi, the motor kept rumbling and spluttering and oil came back in their faces at the rate of a quart a minute. Jack passed Erik a piece of cheesecloth every few minutes so that he could wipe the oil off his goggles. Smoking with vaporized lubricant and spattered with red-hot metal, the good old cruiser shivered and staggered and shimmied and kept right on going. Every once in a while the motor stopped dead, but instead of ‘freezing solid’ it would grapple with its terrible cough and come to life agam. At last Erik saw Karachi looming ahead and knew he had brought his ship safely through a serious crisis. Meanwhile the Chwago had sped on to locate the landing field, so that the New Orleans would not have to do any unnecessary maneuvering before coming to rest.

Nelson gave a remarkable exhibition of airmanship. First he would shoot down for five hundred feet or so to ease his engine when the temperature rose to the point where there was danger of the motor freezing, then he would straighten out and use his throttle to bring the plane up most of the distance lost in dropping. Then he would shoot off again. For seventy-five miles he kept this up, until he successfully brought the New Orleans to the ground at Karachi, covered with oil from nose to tail and even dripping off the rudder, and punctured with holes. Over eleven gallons of oil were thrown out, much of it into the faces of Erik and Jack. It took them several days to get it out of their hair.

On the evening of July 4th, the Royal Air Force entertained us at dinner, and Commander Hicks held a banquet in our honor, and in a witty speech one of our hosts said he had seen all of the expeditions that had set out to fly around the world. He mentioned several British, a couple of French expeditions, Italian attempts in the course of which five or six planes were smashed, and a Portuguese expedition. He said they had all passed through Karachi, flying from west to east. “But you Americans,” he added, “have the reputation of trying to do everything differently from any one else, and here you are flying around the globe in the opposite direction. However, you seem to have the right idea, for you have already flown farther than any of your competitors.

ACROSS THE ARABIAN DESERT

Below us passed many another caravan. ‘When the airplane comes into its own, as it is sure to do within a few years. one wonders what will become of that most picturesque of men, the desert Arab. Journeys that take him two months can now be made by airplane between sunrise and sunset. Within a short time, planes will be so cheap that even the Bedouin sheik will own one, or several. Then the day of desert raids and racing camels will have passed, because the sheik with his swift pursuit planes will be able to overtake and wipe out his enemy within a few minutes. Both the British in Mesopotamia and the French at Aleppo told us that the Arabs were extremely interested in flying developments. When taken up in a plane the average sheik keeps begging the pilot to go higher and faster.

Long before this, we had already become convinced that the airplane is destined to have an immense influence on the peace of the world. The speed with which men will fly from continent to continent will bring all peoples into such intimate contact that war will be as out of date as the cuneiform inscriptions of the ancient civilizations that the shadows of our Cruisers were passing over.

Hungary

It was a disappointment to us to find that the Queen of Rumania and her beautiful daughters were not in

Bucharest. Far away in Burma, Jack Harding had read in the Rangoon ” Gazette” that the rumored marriage of the Prince of Wales to a Rumanian princess had fallen through. This had sort of set Jack thinking and naturally we had done nothing to discourage him. So it was a shock to find that the princesses were away at their country seat. However, next day, we received a message from Her Majesty, sent down by special courier from her summer castle in the Transylvanian Alps, inviting us to spend the weekend with her. Very-reluctantly we had to send our regrets, explaining that we were hurrying around the world. Later on, we added, we hoped we might have the opportunity of accepting Her Majesty’s gracious hospitality. So you see how close Jack came to living happily ever after!

From Vienna to Paris

From here all the way to Paris, ” Les” and I were sailing in an airway we had used many times before – skies once flecked with white puffs from bursting “archies,” and echoing day and night, with the scream of projectiles on their mission of death.

Turning north from Nancy we flew over the famous Saint Mihiel salient where the first American army to visit Europe fought its first great battle under the leadership of its own generals. From Nancy all the way along the old Hindenburg Line, the earth was still scarred by the War, but most of the fields were green now and leaves grew on the trees, not as in the nightmare days of 1918, when birds, beasts, and vegetation had been blown away by the guns.

Past Verdun we flew. Looking over the edges of our cockpits we saw the graves of those gallant Frenchmen who said, “THEY SHALL NOT PASS!” and stood like steel while wave after wave of a mighty army spent itself against their devoted ranks. Then on to the Argonne Forest. It seemed difficult to realize that it was in these same skies that Ball, Guynemer, Bishop, Fonck, Nungesser, and our own Eddie Rickenbacker and Frank Luke, and thousands more of our fellow airmen – and many equally gallant enemy airmen also – used to dive down, spitting tongues of flame, to send their adversaries crashing

to destruction. Our thoughts were with them as we turned west toward the valley of the Marne, for we realized that it was by their efforts that what we were doing now had been made possible.

I was thinking of my pals, who had fought their last fight here, for La Belle France, when Ogden pointed to a fleet of airplanes approaching us. I’ll admit that my heart skipped a beat or two, while I brought myself out of my reverie and remembered that it couldn’t be Richthofen’s Flying Circus. Instead, it was a fleet sent out to escort us to Paris.

Lieutenant Ogden Waving the Tricolor Flag of France as the Boston Taxied across Le Bourget Aerodrome on Bastille Day. (a/i enhanced)

It was the afternoon of July 14th, Bastille Day, and thousands of people were cheering and waving flags when at five-fifteen we taxied up to the hangars at Le Bourget. An hour passed before we could get a chance to do any work on our planes because it took that long for us to shake hands with the many high French officials and foreign diplomats who had come out to greet us.

During that hour on the outskirts of Paris we met more generals, ambassadors, cabinet ministers and celebrities, than we had encountered in all the rest of our lives. There were so many of them that we couldn’t remember their names, despite the fact that they were all men whose names are constantly in newspaper headlines.

Flying in a perfect triangle above us, the great planes come, with the sunlight glinting on their wings. One by one they drop to earth with the light grace of a dragon-fly. Slim khaki figures emerge from the cockpits – one cries, ‘Just in time for tea! ‘Then Smith asks who are winning in the Olympic Games. Wade

lifts his goggles with a placid air. Nelson pulls off his helmet, watches the camera-men, and then, with a full-throated laugh, takes a kodak and shoots back in return.

There are cries of ‘Vive la France!’ and ‘Vive l’ Amérique!’ But where are the heroes? They have vanished. ‘Feeding their horses,’ someone explains. And in fact, the Fliers have left the throng, and with a gesture that is simple as it is symbolic, they are wiping down the engines to which they owe a part of their glory”. – Andrée Viollis, in Le Petit Parisien

After we had refueled, ‘Wade continues,’ we were whirled to a hotel in the staff cars of the French Aviation Service, given a few minutes in which to clean up, had an American dinner in our rooms while dressing, and then were ushered into a box at the Folies Bergéres. ‘Dead tired after having flown more than ten hours that day, as soon as we had made ourselves comfortable in the box, we promptly fell asleep. The whiskers of the Assistant Cabinet Minister, who was sitting near me, bristled with astonishment at my behavior: I know they did, because he gave me a nudge in the ribs during a particularly spectacular scene. I opened my eyes, looked at him and then at the celebrated Folies, who were prancing along a runway out over the heads of the audience. “Huh,” I said, too tired to take interest, and then went back to sleep. The Paris newspapers commented on this and Le Matin said: “If the Folies Bergéres won’t keep these American airmen awake, we wonder what will?

Paris to London

ALL THE WAY ACROSS THE ENGLISH CHANNEL, OGDEN WIGWAGGED SOFT NOTHINGS TO A FLAPPER IN A NEIGHBORING PULLMAN PLANE (a/i enhanced)

On our way across the Channel, the clouds had parted once or twice, just enough to enable us to catch a glimpse of angry seas lashing against Cape Griz Nez and Dover. We shed a Hollywood tear as we saw them, out of sympathy for the poor travelers wallowing in the steamers below. There we were, never uncomfortable for a moment, happy as birds, and reveling in scenery as grand as the views from the tops of the Alps. Within a few years, these cross-Channel ships of horror, where you are given a basin with your deck chair will be as obsolete as the galleys of the Phoenicians.

When we stepped out of our cockpits at seven minutes past two, we were mobbed by photographers, and autograph collectors, for the crowd had broken through the police lines. But in ten minutes the “bobbies” had the mob corraled, and one of the first to welcome and congratulate us was Mrs. Stuart MacLaren, wife of the British world flier.

England to Iceland

Now that the World Flight had completed two thirds of its course, General Patrick and his advisers in Washington were anxious to eliminate every possible risk of failure by stationing destroyers along the route from the Orkney Islands to Labrador. Ahead, lay the most dangerous lap of the journey. Airplanes had never been to either Iceland or Greenland, and the Fliers were sure to encounter skies heavy with fog there and seas full of icebergs.

Orkney Islands

It was not until Saturday, August 2nd: continued Arnold, ‘that the weather cleared sufficiently to warrant our attempting the hop to Iceland. At 8.34 A.M. we set out by way of the Faroe Islands. Hardly ten minutes out of Kirkwell we ran into thick fog. Although we came down as low as five feet off the water, we couldn’t escape it. Then it cleared for a moment and we plunged into a heavy rain squall: beyond, we again met fog. Climbing up to about twenty-five hundred feet, we got above both fog and rain. Looking around for the others, we saw the Boston, but there was no sign of the New Orleans.

They Returned to the Orkneys.

A little later the following wireless message came through from Iceland: Got into propeller wash in the fog, went into a spin, partially out of control, came out of it just above water. Continued on, landing at Hornafjord. All O.K. – NELSON

We were overjoyed at hearing they had got through to Iceland. Later, we learned that they had had a narrow escape.

The following day after leaving the Orkneys again:

There was a stiff breeze on our tail and we were clipping off a hundred miles an hour, says Les Arnold.

Leigh always flew at our right, keeping the Boston a few yards astern of us, so that I could easily check his position. But at eleven o’clock I glanced round and the Boston had vanished. She had been in her usual place just a moment before. So we looked around to the left and there we saw Leigh and Hank turning back, heading into the wind, and gliding for a landing on the ocean.

We, of course, turned immediately, circled as close as we dared, and watched them land. In spite of a long swell and mountainous waves, Leigh brought her down perfectly. Flying low to get her signals, we saw oil on the water and all over the plane.

From Leigh Wade of the Boston:

When we reached the water, I discovered how deceitful the sea is when you are above it. At five hundred feet it had looked fairly smooth. But when we landed, we found it so rough that the left pontoon nearly wrapped itself around the lower wing, and snapped two of the vertical wires.

Smith and Les were circling around us, and I was afraid that they might land and crack up also. That was why we signaled so emphatically for them to stay in the air. We indicated to them that our engine had failed, that our repairs could not be made at sea, and that they should go on.

PACIFIC, WADE LITTLE DREAMED

OF THE TROUBLE HE WAS TO ENCOUNTER ON THE WAY TO ICELAND (a/i enhanced)

But within a very few minutes after we had come to this satisfactory conclusion, the weather changed for the worse. The sea became increasingly choppy, and it looked as though the wings would dip under the waves and buckle up at any moment.

Rescued by the USS Richmond:

The signal was given and I can recall the feeling of joy that swept over me as I saw our beloved plane rising off the water. Then the crash came. The tackle was wrenched loose from the main mast, and the plane fell. Fortunately all the sailors had cleared away from underneath and no one was injured. Our task now was to keep her afloat because the fall had broken the pontoons. Men went aboard at once with veneer, fabric, and “dope” to make emergency patches while others operated the bilge pump. We

took everything loose off the plane, such as baggage, tools, and spare parts, and also decided to disassemble her by sawing off the wings and pontoons before attempting to hoist the fuselage onto the deck. ‘But fate was against us. The wind But fate was against us. The wind had been increasing in violence and it soon became impossible to work on the plane. She tossed so violently that it looked for a bit as though the men on her were going to lose their lives. One of them did get carried overboard, but two of his companions seized him before he had been carried away. Then they all returned to the cruiser, and we saw that our only chance was to attempt to tow her to a lee shore in the Faroes and disassemble her there.

Shortly after five o’clock I was aroused and told that the plane had capsized. This had occurred after the front spreader bar had broken loose and allowed the pontoons to come together. All of the tanks had been left open in the event of just this sort of thing happening, so they would fill with water and cause the plane to sink instead of drifting about as a menace to shipping.

When this occurred we were within a mile of land – so near and yet so far I Alas, we were forced to abandon her, and at 5.30 A.M. we cut the tow lines, bade farewell to our friend who had carried us so far round the globe, and headed for Iceland with heavy hearts.

Iceland to Greenland

When Smith received Wade’s wireless that the Boston had gone down after all efforts to save her had failed, there was mourning at Homafjord, for the boys knew how Leigh and Hank were feeling after coming twenty thousand miles round the world and then losing the Boston through no fault of their own. They realized also that nothing but blind chance had prevented the accident happening to one of them. In England, where they had changed motors, Wade and Ogden happened to be the first to get their plane ready to install the new engine. Four new motors lay there on the floor of the Blackburn aircraft factory, and as luck would have it Wade selected the one that failed. Just where the weakness developed will never be known, but the probability is that the oil pump shaft broke, thus preventing the oil from circulating.

Navigation

Although the rain and wind were coming from the north and west, we knew they might shift any moment. So, of course, it was impossible to tell where we might drift. It had been our custom to cut our maps into strips and roll them so they would be easy to handle in the cockpit as we flew. They were large scale, and whenever flying over thoroughly explored regions showed every village, mountain, stream, or other landmark. The strip we had along on this hop to Iceland included nothing but the Orkneys, the Faroes, and the eastern end of Iceland. So we could only make a rough guess as to how far we were from the nearest mainland.

We now did a thing that caused the rest of the fellows afterward to dub us the world’s greatest optimists. “Hank” climbed out of his cockpit, hung on to the edge of it with one hand, opened the tool compartment, and ferreted out a very small-scale National Geographic Society map of the world which we had carried all the way with us. On this map we measured off the distance we were from the coast of Norway, and calculated that with favorable winds we might possibly exist – until we drifted to those shores, providing, of course, that we could keep the plane intact that long.

Nelson and Wade pay tribute to Smith for his skill as a navigator. Indeed, everyone who has flown with him declares that his instinct for direction is like that of a homing pigeon.

Iceland to Greenland: The Longest Leg

Captain Lyman A. Cotton, in command of the Admiral’s flagship Richmond, described this stretch from Iceland to Greenland as ‘the longest and most difficult leg of the trans-Atlantic flight:

Eight hundred and thirty-five statute miles across an ocean covered by ice and beset with fog and cold, it was truly a flight to test the skill and courage of the hardiest aviator. As the Chicago and New Orleans, swept by the Richmond close enough to the bridge for every feature of the aviators to be recognized, it made a lump come in one’s throat to realize how fragile were these man-made ships of the air and how many miles of restless waters lay ahead of them before they reached Fredricksdal.

Our next message from Schultze said that the Gertrude Rask had finally broken through the ice and reached her destination. This was a great relief to us and somewhat surprised the newspaper men, who had become decidedly pessimistic and were laying wagers that the Flight would have to be abandoned. I believe that only the Washington Star correspondent, out of all the reporters, still had faith that we would finish the trip.

As we were returning to the hotel, a sheet of radiograms was handed to us announcing that weather conditions were at last favorable. So without a moment’s sleep or rest that night, we climbed into our cockpits and at 6:55 set out for Greenland on the longest and most hazardous “hop” of all, a flight that was to overshadow all previous experiences on our way around the world.

In the meantime, on August 11th, the advance agent of an Italian Flight had arrived, and shortly after midday on the 16th, Signor Locatelli, a former lieutenant in the Italian air service, an ace with a brilliant war record for bravery and daring, and a member of the Chamber of Deputies in Rome, arrived in Homafjord from the Faroe Islands in a super-flying boat, a sister to the two planes to be used later by Amundsen and Ellsworth on their attempt to reach the North Pole. On August 17th, while Admiral Magruder’s squadron was getting into position between Iceland and Fredricksdal, Locatelli reached Reykjavik. We were much impressed by his business-like, twin motored monoplane with its all-metal hull. It appeared to be the most efficient plane for long-distance flying that we had ever seen, and Lieutenants Locatelli and Crozio and their two assistants were dashing fellows.

The Chicago and New Orleans approaching Greenland:

As we neared the coast, the ice increased until we were flying over a seemingly endless expanse of fantastic bergs of every size and shape. Some looked as high as the Chicago Tribune Tower or the Woolworth Building. Had we seen them under different conditions the sight, no doubt, would have inspired us. As it was, they were terrifying, because we never saw them until we were right upon them. We had to fly as low as thirty feet off the water in order to keep our bearings at all, so you can just imagine the close shaves we had while playing tag and leap-frog with those icebergs!

Three times we came so suddenly upon huge icebergs that there was no time left to do any deciding. We simply jerked the wheel back for a quick climb, and were lucky enough to zoom over the top of it into the still denser fog above.

Some of the mountains along the Greenland coast rise to eight and ten thousand feet. So had we climbed to our limit there still would have been plenty of room for us to crash into the top of one of those mountains just as Major Martin had done in Alaska.

But finally what we feared would happen, did happen. Diving through a small patch of extra heavy fog that was clinging close to the water, we emerged on the other side to find ourselves plunging straight toward a wall of white. The New Orleans was close behind us with that huge berg looming in front. I banked steeply to the right while Erik and Jack swung sharp to the left. Les shouted, “Hold on, God,” and I’m sure I did some rapid praying myself. Both left wings seemed to graze the edge of the berg as we shot past it. And in far less time than it takes to tell it the two planes were lost from each other.

OVER GREENLAND’S ICY MOUNTAINS (a/i enhanced)

Finally, we arrived over where, according to our charts, we thought Fredricksdal ought to be, and watched anxiously for an opening in the clouds. We circled around several times, and then the All-Wise Providence, who had already spared our lives a dozen times on this day’s journey, parted the clouds for us so that there was a shaft of light extending down to the sea.

Throttling down, we spiraled through the providential cloudrift and landed alongside her at five-thirty in the afternoon. Finding that we were away out at the mouth of a fjord where the water was exceedingly rough, we taxied several miles up the fjord between the snowy mountains, and climbed out of our cockpits where we had been strapped for those eleven hours that had seemed like eleven years.

THE CHICAGO AND TIHE NEW ORLEANS MOORED IN THE ICEBERG-INFESTED HARBOR AT FREDRICKSDAL JUST AFTER COMPLETING THE LONG AND HAZARDOUS FLIGHT FROM ICELAND TO

GREENLAND (a/i enhanced)

Neither of us said a word about Erik and Jack, but we were thinking of little else. So narrow had been our own escape that it seemed hardly possible that Providence could bring them through in safety also. We simply couldn’t see how any one could be as lucky as we had been.

But forty minutes later, we heard the welcome hum of a Liberty, which meant that Erik and Jack were arriving. Imagine how glad we were to hear that old familiar sound in the sky! It sounded like a hymn of triumph. No choir of celestial angels could have sounded half so beautiful.

The Lost Italians

Captain Cotton, skipper of the flagship Richmond, tells us what happened on that eventful night: Midnight. Cold, and cheerless, The Richmond ploughing through the trackless sea one hundred and twenty miles east of Cape Farewell, Greenland, searching for a tiny object bearing four human lives, Just now for three and a half days. A momentary flicker of light on the horizon ten miles away. The Richmond turns and speeds toward the spot, throbbing with her hundred thousand horsepower. A red star, fired into the air, lights up our decks with lurid light, as officers, men, correspondents, and camera men rush up on deck half-clad, hair disheveled, with heavy overcoats and trailing blankets hastily thrown around them. An answering star from the darkness ahead. Can it be that the lost are found? Can it be? Our searchlights feel along the horizon, groping over the hostile sea that is loath to surrender its prey. The light touches a small object, bobbing about like a cork on the water. All eyes are strained toward the plane, through moments of tense silence. How slowly it seems to draw near! The beams of our searchlights catch it again as it rises to the crest of a breaker, and this time we see the red, white, and green rudder of the Italian monoplane. One, two, three, four – the crew are all visible now. All are alive and safe!

We can imagine with what a sense of triumph Captain Cotton rang down the ‘Stop’ signal to the engineers, when success thus crowned his efforts after eighty hours of search. The Richmond pulls up, with a surge of water from her reversed propellers, not ten yards from the Dornier-Wall and is greeted by a veritable salvo of Italian. A line is tossed from ship to plane. (Locatelli subsequently said, ‘This line was like the first thread connecting us with life again.) Helping hands are extended, for two of the crew are so exhausted that they have to be lifted limply on board in nets. Movie-men crank their machines in the light of the aurora borealis which is dancing it’s strange reel in the Arctic sky. There under the northern lights, on the Richmond’s deck, stand Locatelli and his crew, heavy-eyed, and utterly spent, but safe. For three long nights they have kept their watch with Death in a sea-swept cockpit: now they are in the world of men again.

Out of the wreckage of the monoplane, Lieutenant Locatelli carried his country’s flag, which he presented to Admiral Magruder. Later on, when he met the American pilots in Boston, after mutual congratulations, he said that in his opinion the navigation of the Chicago and New Orleans through that terrible and blinding weather was an epochal feat which will mark a point in the history of air

navigation. Nor is the historian inclined to dispute Locatelli’s opinion: Smith and Nelson, Arnold and Harding, remained in the air for eleven hours of intense nervous tension during this long flight through fog and storm.

The heavy seas had taken their toll of the flying boat, so Locatelli chose to destroy it by setting it afire. That same day, the Americans learned that Major Zanni, Argentina’s entry, had crashed near Hanoi and was out of the race.4

By the time they reached Fredricksdal, they had been without sleep for forty-two hours. Surely no adventure over earth, or air, or water has ever called for more grit than this!

Whenever the wind died down, the air would be filled with billions of tiny gnats. They were the most trouble some brutes you ever saw – worse than tropical insects. They flew into our eyes, up our noses, buzzed in and out of our ears, and we had to talk with our lips shut, to keep them from swarming into our mouths. In fact they were so bad that we finally couldn’t work at all until we got some netting draped over our heads and tied around our necks. It seemed odd to find all these flies in the Arctic, but the Danes told us they were always troubled with them during the short Greenland summer.

Greenland to Labrador

FROM GREENLAND TO LABRADOR, NORTH AMERICA (a/i enhanced)

It was quite a tricky take-off, too, for we had to dodge in and out between the icebergs. But we made it, and for two hours flew along the bleak coast of Greenland, encountering winds that reminded us of the “Willie-was” of Alaska. Nearly every time we rounded a mountain, a terrific gust would strike from the shoulder of a fjord and knock us all over the sky.

It was at 8:15 on the morning of August 31st, says Smith, ‘that we left Greenland on the flight that was to

land us on American soil. From the fjord at lvigtut we flew over Davis Strait and five miles from shore ran into a fog-bank. However, we knew that the weather was clear on the Labrador side of the strait, so we calculated that the fog would not last long. After thirty minutes flying, we came out of it near an iceberg the size of a mountain, that had been reported to us, and had perfect weather for the greater part of the way.

It was good flying weather and all was going well when the cold hand of Failure suddenly tried to claw us down. We were two hundred miles off Labrador when this happened. Our motor-driven gasoline pump failed, and five minutes later our wind-driven pump also gave out, making it necessary to turn on the reserve tank, containing fifty-eight gallons of gas, or enough for over two hours.

I throttled down and shouted to Les that our one hope of maintaining the supply in the reserve tank and

making shore lay in the “wobble-pump,” which is installed in all the planes for just such an emergency and is manipulated by hand. Les was already stripped to the waist. He laid hold of that handle and pumped with it for dear life.

I watched the overflow with a blessed sense of relief. Les has the strength of a lumberjack, otherwise he could never have done what he did. For nearly three hours he pumped without pause or intermission, supplying life-blood to the engine, while I flew on greatly worried about the loss of oil that had smeared the side of my ship. Nelson signaled me about this shortly after leaving Greenland, and I was praying for it to hold out. Only the fact that I had put in more than usual, because it was a new motor, enabled us to reach shore, with tank practically empty.

An hour out from Icy Tickle, our destination on the Labrador coast, we ran into a forty-mile wind that cut

down our speed and made things even worse for Les, who by that time was lathered in sweat like a Tia Juana two-year-old, and almost “all out.” But he stuck to the pump. It is wonderful what guts will do for a man – and the sight of his native land over the starboard fuselage! ‘We reached Icy Tickle, at 8:00 P.M. on August 31st, after a 660-mile flight lasting six hours and fifty-five minutes. So that was that. We were in America.

A launch came out from the Richmond and took us ashore after we had moored. We had landed after our

travel, like the Pilgrim Fathers, on a large rock, but I’m afraid our first actions were not as edifying as theirs. We were just too darned happy for words.

Although Les Arnold had been able to celebrate the Flight’s arrival at Icy Tickle by a step-dance, and said nothing about the condition he was in until the official formalities were over, at the end of that time he nearly collapsed from muscular exhaustion and heart-strain. The naval medical officers took him in hand, had him massaged, and sent him to bed.

From the President:

Your history-making flight has been followed with absorbing interest by your countrymen and your return to North American soil is an inspiration to the whole Nation. You will be welcomed back to the United States with an eagerness and enthusiasm that I am sure will compensate for the hardship you have undergone. Your countrymen are proud of you. Your branch of the Service realizes the honor you have won for it. My congratulations and heartiest good wishes go to you at this hour of your landing. – CALVIN COOLIDGE

From the Secretary of War came a radio to each member of the Flight, congratulating him on his bravery, hardihood, and modesty. More particularly to you as leader of the Flight, added the Secretary of War to Smith, I desire to say that your courage, skill, and determination have shown you to be a fit successor to the great navigators of the Age of Discovery. The Air Service, the War Department, and the whole country are proud of you.

Flying down the west coast of Newfoundland:

Several miles from our destination we were met by a Canadian Royal Air Force plane whose occupants waved us an airy salute and then escorted us to Pictou. As we circled over the harbor at 5:40 P.M. we saw Wade’s new plane, the Boston II, that had been sent up to Nova Scotia by General Patrick in order that “Leigh” and “Hank” might make the rest of the flight with us. Every whistle in Pictou was tooting its shrillest and the shore was lined with cheering Canadians when we taxied to our moorings. Wade and Ogden were the first out to meet us and with them were our friends Lieutenants MacDonald and Bertrandias, the officers who had ferried the Boston II from Virginia to Nova Scotia. Les and MacDonald had been “hunkies” at various aviation camps around the U.S.A. since 1917, so they were overjoyed at seeing each other again.

The trip to Boston was uneventful. As we circled over the historic Harbor and Bunker Hill, we saw a throng of people evidently waiting for us at the landing-field. Although we couldn’t hear a thing owing to the roar of our motors, we could see fire-boats spouting fountains of water, streaks of steam shooting up from factories, ocean liners, tugs, and ferryboats, and puffs of smoke coming from the warships beneath us, firing 21 guns salutes.

The first thing that happened when we stepped ashore at Boston, says Smith, was that someone shoved a radio microphone in front of me. I looked at it dumbly and then asked: “What am I supposed to do with this?” Of course the “mike” was turned on, so these were my first words to the American public. Then General Patrick, or somebody, explained that Mother and Dad were out in Los Angeles listening in and that I was supposed to make a little speech. I simply said: “Hello, folks, I’m glad to be home,” and let it go at that.

After receiving the greetings of our Chief, who had sent us forth to explore the airways of the earth, we were greeted by the Governor of Massachusetts, the Mayor of Boston, the Assistant Secretary of War, the Corps Commander, and any number of other officials. Nelson’s brother Gunnar, a mathematician of note, had flown all the way from Dayton, Ohio, to welcome him, and a quiet Englishman came up who turned out to be none other than the British World Flier, Major Stuart MacLaren. In addition to thanking us for sending his spare plane from the Kurile Islands to Burma by destroyer, he told us that he was on his way home to outfit another round-the-world expedition. That’s the English spirit.

As we flashed through the streets, the sidewalks were jammed with cheering throngs. It was all totally unexpected. Of course we hadn’t seen a paper in Iceland, Greenland, or Labrador. In fact, we had only glanced at a few foreign journals since leaving Seattle, so we hadn’t the faintest idea there was going to be all this enthusiasm.

We pulled up at Boston Common, and there, in addition to addresses of welcome, we were showered with gifts, such as keys to the city, sabers, huge Paul Revere bowls, American flags, silver wings, watches, and even silver mesh-bags for our mothers.

When we were each presented with a great Stars and Stripes in silk, a dramatic incident occurred. Erik, the only naturalized American among us, bent gracefully over the folds of his country’s flag and kissed it.

Later that night from Lowell Smith:

Dressing that night was quite an undertaking. The telephones in all six rooms were all ringing at once, and they never stopped. So we put a bell-boy on each. Crowds of officials and friends surged in and out. Bell-boys dashed hither and thither. Pandemonium reigned. But we certainly were sitting on top of the world for once in our lives.

That night we dined quietly with General Patrick, and between courses a radio microphone was served up to us on a platter so we could chat with the world at large. Whenever I get in front of one of these instruments, my gas pump refuses to feed, lung compression drops to zero, my heart starts to knock, and the old think-box freezes!

Guess we’ll have to fly around the world again, said Smith, with that wry smile of his, when he had finally brought the Flight safely to Seattle, – just to recover from all these receptions! For boys who had undergone six months of nervous and physical strain, during their Flight around the globe, the ordeal by banquets which they passed through while crossing America, came as a severe and unforeseen test of endurance. Hand-shaking and speech-making have exhausted many a celebrity, men whose whole lives are spent in the public eye, but of such things Smith and his companions knew nothing and cared less. They had flown twenty-three thousand miles around the world, and still had more than three thousand miles to go in airplanes that in spite of their sturdiness had long since passed their allotted span. Constant attention to business was therefore necessary by day; while by night they bad no rest, for at each and every step between Boston and Seattle they met old friends and new ones, responded to toasts, gave interviews, were the center of civic functions, and lived a life which is known to be perilous to nerves and digestion. All this in addition to the routine of flying across a continent, no mean task in itself.

For these reasons, a living buff er of bonhomie and tact was required to stand between the boys and the public. This shield was forthcoming in the person of their social representative, the charming and disarming Lieutenant Burdette Wright.

“Birdie” is as able a diplomat as he is pilot, says Smith, – and that is saying a whole lot. We were often late in arriving at the various cities on our schedule and committees naturally were peeved about having to arrange new dates for their banquets. But “Birdie’s” smile always allayed their annoyance and we owe him a very hearty vote of thanks for the way he looked after us.